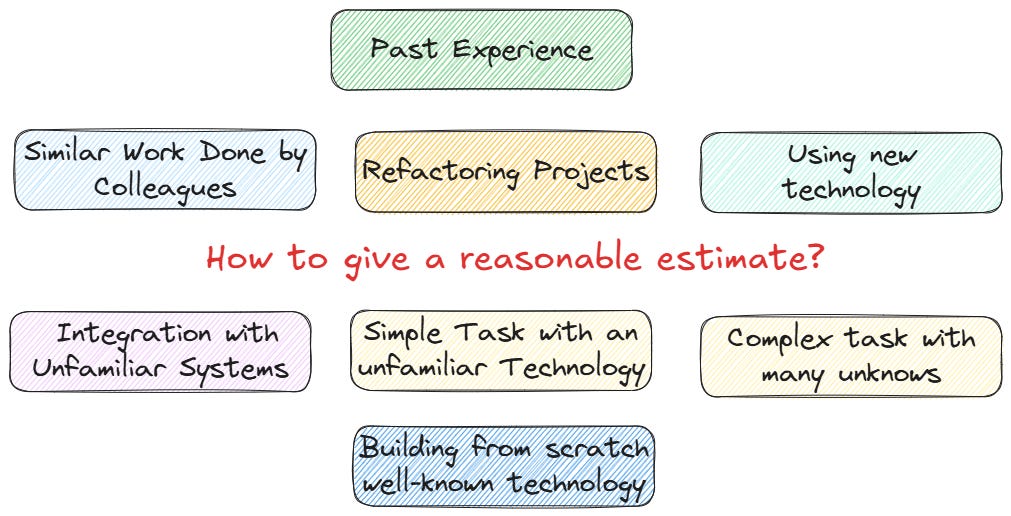

How to Estimate the Duration of a Task

Eight strategies you can use to give better estimations as a software engineer.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to the 147th issue of the Polymathic Engineer.

"How long will this take?" is a question that makes most software developers feel bad, especially if they are reading a bug report or a new feature request that is difficult to understand. Despite that, this question will be asked of you many times.

The reality is simple: businesses need to…