Software Design Principles That Matter

A tour over Open-Closed Principle, Dependency Injection, and Inversion of Control.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to the 157th issue of the Polymathic Engineer.

Every software engineer has seen something like this happen: you write a feature, ship it to production, and everything works great. Then, a few weeks later, you get different requirements. You have to support a new use case, but you find out that your code is not ready.

You open the codebase and realize that to make this change, you need to update many classes and method signatures, and you hope you don’t break anything in the process.

What should have been a simple extension turns into a risky refactoring project. This is where good software design principles make all the difference.

In this article, we’ll explore three fundamental principles that help you build flexible, maintainable code: the Open-Closed Principle, Dependency Injection, and Inversion of Control.

By the end, you will hopefully have a better understanding of how to write code that welcomes change rather than fights against it.

This O’Reilly book on data engineering patterns is a great way to start learning about how to build large-scale APIs and data pipelines. You can get it for free thanks to the Buf team, who sponsored this newsletter issue.

Buf helps teams manage their Protobuf APIs. Manually generating `.proto’ files and putting them under version control works at a small scale. But if you have several teams using Protobuf and lots of API users that need to pin to specific versions, it gets hard.

The 𝗕𝘂𝗳 𝗦𝗰𝗵𝗲𝗺𝗮 𝗥𝗲𝗴𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗿𝘆 provides centralized API management for Protobuf APIs, giving you a single source of truth and policy enforcement.

Download your free copy if the book here.

Open-Closed Principle

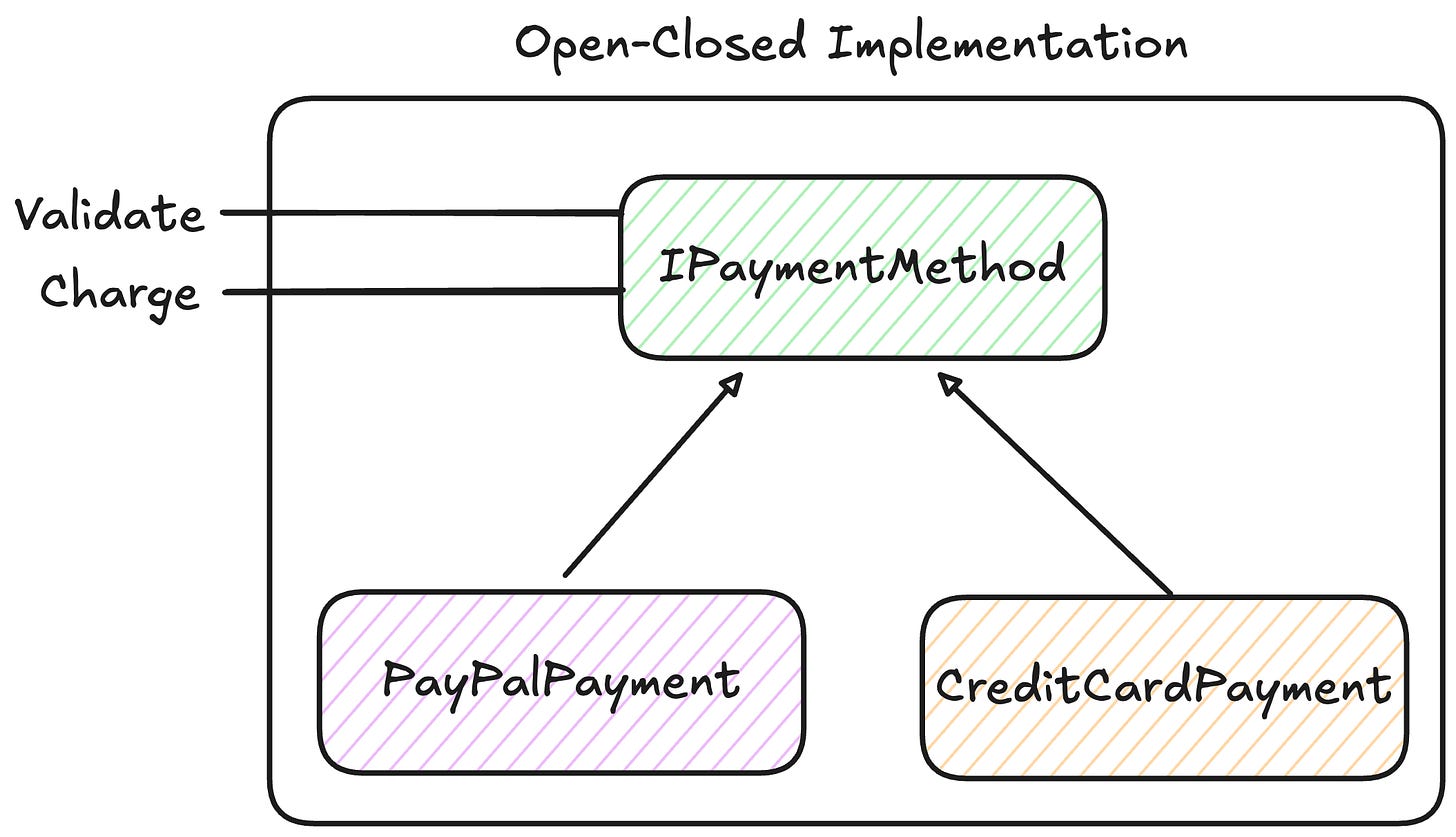

The Open-Closed Principle states that code should be “open for extension, closed for modification. This means you shouldn’t have to change the code to add new features.

The goal is to write code that doesn’t need changes when requirements evolve. What this means can be better understood through an example.

Let’s suppose you are building a payment processing system. At first, the requirement is simple: handle credit card charges. You might start creating a CreditCardProcessor class that handles everything:

public class CreditCardProcessor

{

public void ProcessPayment(decimal amount, string cardNumber)

{

if (!IsValidCard(cardNumber))

throw new InvalidCardException();

ChargeCard(cardNumber, amount);

LogTransaction("CreditCard", amount);

}

private bool IsValidCard(string cardNumber) { ... }

private void ChargeCard(string cardNumber, decimal amount) { ... }

private void LogTransaction(string type, decimal amount) { ... }

}This works fine until you get a new requirement: support PayPal payments. Then you get another one: support Stripe. Now you are stuck.

It's no longer just about credit cards, so adding all this logic to CreditCardProcessor doesn't make sense. Also, copying and pasting the class to create PayPalProcessor and StripeProcessor doesn't make sense, since it would mean writing the same code twice.

There is no good choice. The solution is to separate the parts that vary from the parts that stay the same. You can create an interface for payment methods, then implement it for each payment type:

public interface IPaymentMethod

{

bool Validate();

void Charge(decimal amount);

string GetPaymentType();

}

public class CreditCardPayment : IPaymentMethod

{

private string _cardNumber;

public CreditCardPayment(string cardNumber)

{

_cardNumber = cardNumber;

}

public bool Validate()

{

return IsValidCard(_cardNumber);

}

public void Charge(decimal amount)

{

ChargeCard(_cardNumber, amount);

}

public string GetPaymentType() => "CreditCard";

private bool IsValidCard(string cardNumber) { ... }

private void ChargeCard(string cardNumber, decimal amount) { ... }

}

public class PayPalPayment : IPaymentMethod

{

private string _email;

public PayPalPayment(string email)

{

_email = email;

}

public bool Validate()

{

return IsValidEmail(_email);

}

public void Charge(decimal amount)

{

ChargePayPal(_email, amount);

}

public string GetPaymentType() => "PayPal";

private bool IsValidEmail(string email) {...}

private void ChargePayPal(string email, decimal amount) {...}

}

Now, to add support for a different payment method, all you have to do is make a new class that uses IPaymentMethod. You don’t change PaymentProcessor or any payment methods that are already set up. The PaymentProcessor is closed for modification but open for extension. The principle allows you to keep more options available and delay decisions about the details, so you don't have to change as much code.

Good examples of the open-closed principle include MVC frameworks such as Spring or ASP.NET Core. These frameworks have also ruled web development because they are easy to use and can be extended. You don't have to change the framework's code to add new tools, create custom filters, or set up custom model binders.

The framework defines extension points through interfaces and abstract classes. You plug in your implementations, and everything works together.

Dependency Injection

Dependency Injection is an excellent technique for reducing coupling and promoting the open-closed principle. Instead of having the class create its own dependencies, it provides references to the things the class needs.

When using dependency injection, you try to know as little as possible. Classes don’t need to know how their dependencies are created, where they come from, or which implementations are being used. It may not seem like a big deal, but this small change makes your code much more flexible.

As an analogy, think about how a streaming player, like Netflix or Spotify, works. The player knows how to display content, control playback, and interact with users. But it doesn’t know about every movie or song that exists. It doesn’t have a hardcoded list of all available content.

The app instead relies on an external information source. Netflix gets the library from a server when you open it. The player stays dumb and doesn't need any change when a new movie comes out.

Let’s look at a code example. Here is an implementation for a notification service that sends emails:

public class NotificationService

{

private EmailSender _emailSender;

public NotificationService()

{

_emailSender = new EmailSender("smtp.gmail.com", 587);

}

public void NotifyUser(string email, string message)

{

_emailSender.Send(email, message);

}

}This might look fine, but the NotificationService is tightly coupled to EmailSender. It knows exactly how to create it, including the SMTP server and port. What if you need to change the email provider? What if you want to send SMS notifications instead of emails? What if you need to test this class without actually sending emails? You can’t. You have to modify the NotificationService class every time.

Here’s the same class using dependency injection:

public interface INotificationSender

{

void Send(string recipient, string message);

}

public class NotificationService

{

private INotificationSender _sender;

public NotificationService(INotificationSender sender)

{

_sender = sender;

}

public void NotifyUser(string recipient, string message)

{

_sender.Send(recipient, message);

}

}Now you can have different implementations, and the NotificationService doesn't know or care which implementation it gets. It just knows it can call Send on whatever is provided.

public class EmailSender : INotificationSender

{

private string _smtpServer;

private int _port;

public EmailSender(string smtpServer, int port)

{

_smtpServer = smtpServer;

_port = port;

}

public void Send(string email, string message)

{

// Send email

}

}

public class SmsSender : INotificationSender

{

private string _apiKey;

public SmsSender(string apiKey)

{

_apiKey = apiKey;

}

public void Send(string phoneNumber, string message)

{

// Send SMS

}

}When used well, dependency injection reduces the complexity of each class, allowing it to focus on its single responsibility. It may seem like you end up with the same code in a different place, but that is exactly the point. By removing the assembly code from your classes, you make them more independent, reusable, and testable.

In practice, dependency injection can be summarized as avoiding the new keyword in your classes and demanding instances of your dependencies through the constructor.

Frameworks like ASP.NET Core have built-in dependency injection containers that automatically create and provide dependencies. But you don’t need a framework to use dependency injection. You can apply it in any codebase.

Inversion of Control

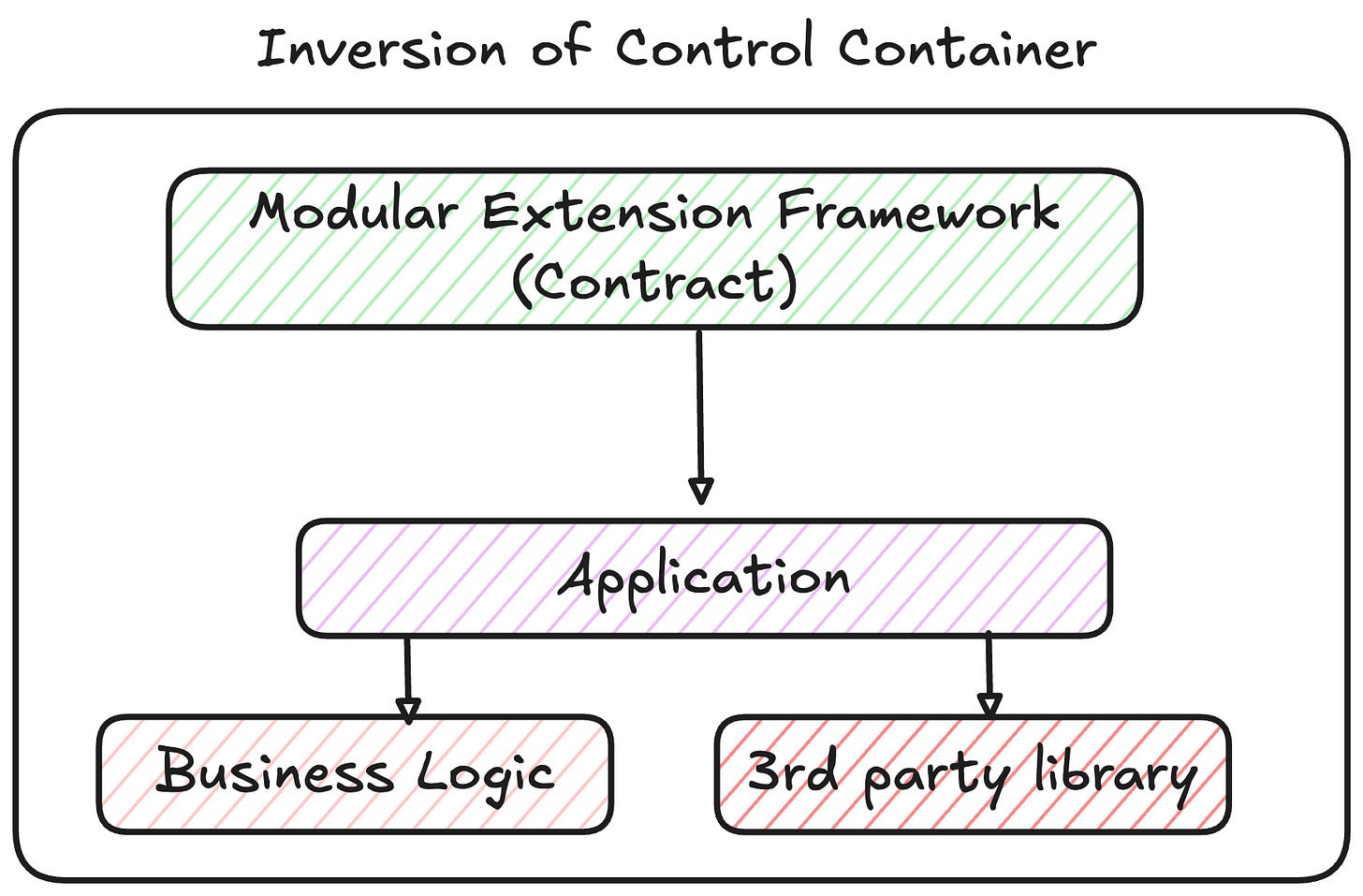

Dependency injection is part of a broader principle called Inversion of Control. The first is more specific and examines how things are made and how their dependencies are assembled. Inversion of Control, on the other hand, is more general and can be used to solve a wide range of issues.

Inversion of Control is a design pattern that removes responsibilities from a class, making it more straightforward and less tightly coupled to the rest of the system. To understand it, think about what it would take to build a web API from scratch in C# without any framework. No ASP.NET Core, no web server, nothing. Just C#.

You would need to write a lot of code. You have to open network sockets, parse HTTP requests, route them to the appropriate handlers, manage threads, handle errors, log everything, and send responses. You need to control the entire application flow.

Now consider building the same API using ASP.NET Core. You don’t write any of that infrastructure code. Instead, you create controllers:

[ApiController]

[Route("api/payments")]

public class PaymentController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly IPaymentService _paymentService;

public PaymentController(IPaymentService paymentService)

{

_paymentService = paymentService;

}

[HttpPost]

public IActionResult ProcessPayment([FromBody] PaymentRequest request)

{

var result = _paymentService.Process(request);

return Ok(result);

}

}The controller doesn’t know when it will be created, who will call its methods, or how the HTTP request gets to it. The framework handles all of that. Your code becomes a plugin to the framework.

This is Inversion of Control. You’re not in control anymore. The framework is. A good Inversion of Control framework has a few key characteristics. You can create plugins or extensions. Each plugin is independent and can be added or removed at any time. The framework can auto-detect these plugins or provide a way to configure which ones should be used. The framework defines interfaces for each plugin type and isn’t coupled to the plugins themselves.

Inversion of Control is everywhere in modern frameworks. Once you start looking for it, you’ll see it in ASP.NET Core, Entity Framework, dependency injection containers, and many other tools you use every day.

Bringing It Together

The three principles we have discussed in this article work together to help you write better code. The Open-Closed Principle gives you the structure. It shows you how to separate what changes from what stays the same using interfaces and abstractions.

Dependency Injection gives you the mechanism. It shows you how to give your classes dependencies rather than have them create their own. Inversion of Control gives you the pattern. It shows you how to build systems where your code becomes plugins to a larger framework.

These principles have been around for years because they work. When you apply these principles, you reduce coupling and complexity, and your code becomes easier to test, extend, and maintain.