Fundamental Graph Algorithms - Part I: BFS

Breadth First Search and its applications: shortest paths, connected components and bipartite testing.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to the 150th issue of the Polymathic Engineer newsletter.

This week, we start a small series of in-depth articles regarding graph algorithms and their applications. In this first article, we will focus on the basic concepts and the breadth-first search algorithm. The outline will be the following:

Graph traversal

Core Concepts

Breadth-First Search (BFS)

BFS implementation

Connected Components

Strongly vs. Weekly Connected Components

Bipartite Testing

Tech interviews are hard. But with the right strategy and resources, it’s a game you can win. ByteByteGo provides a set of practical resources that covers all phases of a technical interview. You can find useful content to ace coding, system design, ML, behavioural, and object-oriented interviews, and much more.

Join the ByteByteGo platform and start your preparation today

Graph traversal

Imagine you get lost in a maze. You need to discover the way out, but you don’t have a map. What strategy would you use? You might choose a direction and go as far as you can along it before going back, or you could go through all the nearby paths in order before going any further. These ideas are at the heart of Depth-First Search (DFS) and Breadth-First Search (BFS), the two most basic graph traversal methods.

Graph traversal is the methodical process of going to each vertex and edge in a graph. This may seem like a simple job, but it is the basis for many algorithms you use every day. Some examples are detecting circular dependencies in your build system, finding connected components in a social network to identify communities, or figuring out the order to run tasks when some need to finish before others. The solution to all of these problems reduces to using the right traversal algorithm.

The main challenge is easy to understand: how do you visit every section of the graph without getting stuck in an infinite loop? In a real maze, you could use chalk to mark walls and avoid doing the same steps over and over again. In a graph algorithm, you use flags to keep track of which vertices you’ve already seen.

The two fundamental approaches to graph traversal differ in how they decide which path to explore next. Breadth-first search uses a queue to examine vertices in order of their distance from the starting point. Depth-first search uses a stack (or recursion) to explore the graph as deeply as possible before backtracking. None of them is better, but they both do their best in different situations.

In this series of articles, we’ll discuss both algorithms in depth, learn about their key properties, and see how they help solve common graph problems. By the end, you will not only know how these algorithms work, but also when and why to utilize each one.

Core Concepts

Before we go into the details of BFS and DFS, we need to understand a few basic ideas that are true for both. The first is the states of the vertices.

During traversal, each vertex exists in one of three states: undiscovered, discovered, or processed. At first, each vertex starts as undiscovered. It gets discovered when we first come across it during the traversal. Finally, it becomes processed after we have looked at all its outgoing edges.

This progression is important because it avoids infinite loops. When we mark a vertex as discovered, we can ignore any edge that is directed to it because the destination has already been put in the list of the vertices to be processed. Similarly, we can ignore an edge that goes to a processed vertex, because it will not tell us anything new about the graph.

Consider a simple triangle graph with vertices A, B, and C. If we start at A and move to B, then to C, we could return to A and repeat forever. By marking vertices, we break this cycle. When we return to A from C, we see it’s already been discovered and stop.

The second thing you need to learn is how to keep track of the discovered but not yet processed vertices. Both BFS and DFS need a data structure to store such vertices, and the choice of the data structure determines the traversal order:

- BFS uses a queue (first-in, first-out), which makes it explore vertices in order of their distance from the starting point

- DFS uses a stack (last-in, first-out), which makes it go deep before looking sideways

This is the only big difference between the two methods. Changing the data structure changes the way the whole traversal works. In terms of Big O, both algorithms run in O(V + E) time, where V is the number of vertices and E is the number of edges. This is optimal because you need to look at each vertex and edge at least once to explore the graph fully.

Last but not least, you should know that the way you store a graph doesn’t affect the correctness and efficiency of traversal algorithms. As we have discussed in one of the previous issues, different kinds of data structures can be used to represent a graph in memory. The two most common are the adjacency matrix and the adjacency list.

Adjacency matrices use a 2D array where matrix[i][j] indicates whether an edge exists from vertex i to vertex j. This lets you look up edges in O(1) time but takes O(V²) space, regardless of the number of edges. This works well for dense graphs or when you need to quickly check if an edge exists. Adjacency lists store the neighbors of each vertex in a list. This saves memory for sparse graphs and makes it simple to iterate over all the neighbors of a vertex. Most real-world graphs are sparse, so this is usually the best choice.

For the algorithms we discuss, we will use an adjacency list representation because it is more common and works better for most situations.

class Graph:

def __init__(self, num_vertices, directed=False):

self.num_vertices = num_vertices

self.directed = directed

self.adj_list = [[] for _ in range(num_vertices + 1)]

def add_edge(self, u, v):

self.adj_list[u].append(v)

if not self.directed:

self.adj_list[v].append(u)

def neighbors(self, vertex):

return self.adj_list[vertex]Breadth-First Search (BFS)

Breadth-first search explores a graph by examining all vertices at distance k from the starting point before moving to the vertices at distance k+1. If you imagine dropping a stone in a pond, BFS is like the ripples spreading outward in concentric circles.

The algorithm is straightforward. You start by marking the initial vertex as discovered and putting it in a queue. Then you repeat these steps until the queue is empty:

Remove a vertex from the front of the queue

Examine all its neighboring vertices

For each undiscovered neighbor, mark it as discovered and add it to the queue

Mark the vertex as processed

The queue is very important here. Because you process vertices in FIFO order, you are guaranteed to explore all vertices at distance 1 before any vertex at distance 2, vertices at distance 2 before any at distance 3, and so on.

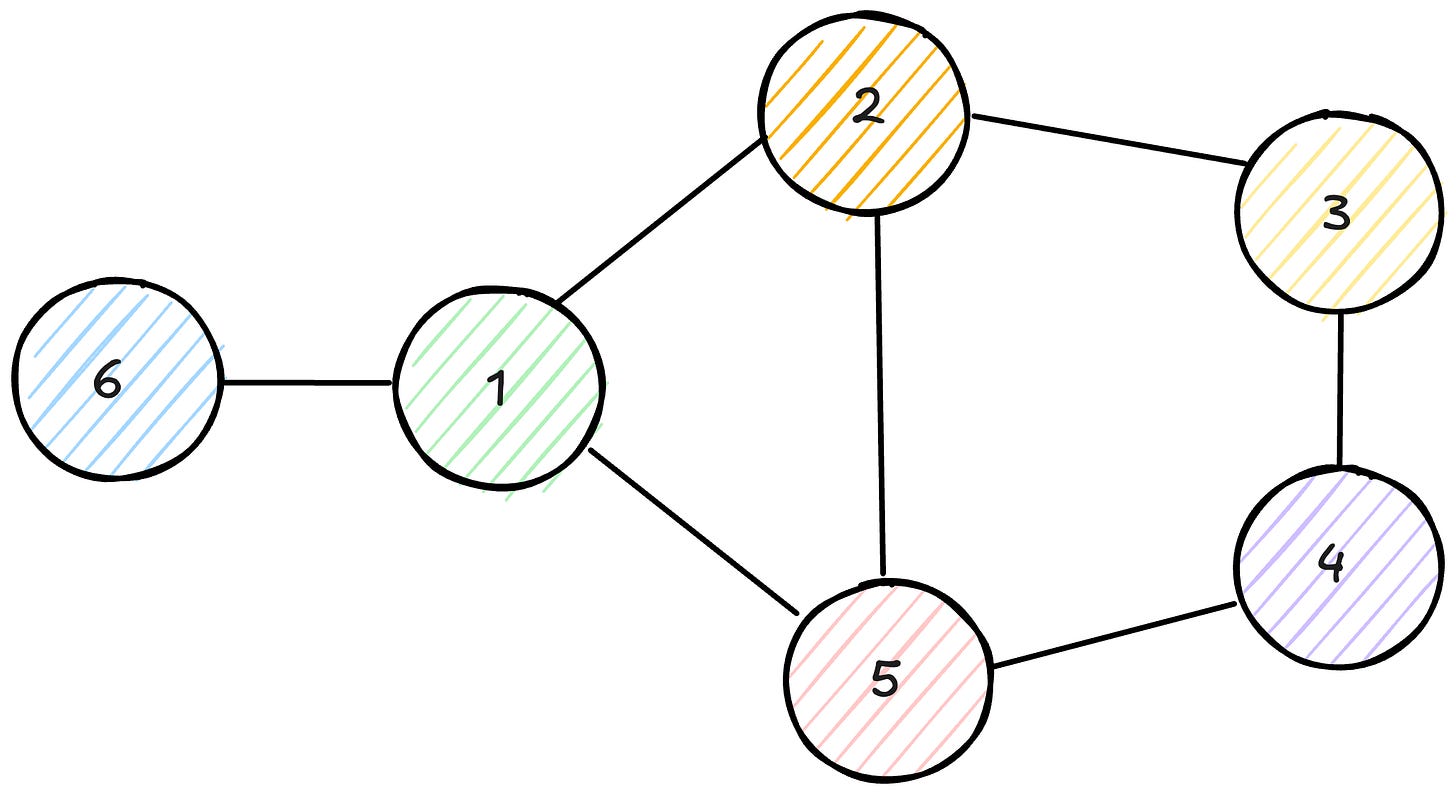

Let’s walk through an example to solidify our understanding. Consider an undirected graph with six nodes and the following edges: (1-2), (1-5), (1-6), (2, 3), (2, 5), (3, 4), (4, 5).

Here is what happens after each iteration:

Initially: queue = [1], Processed: []

Iteration 1: discovered 2, 5, 6 queue: [2, 5, 6] Processed: [1]

Iteration 2: discovered 3, queue = [5, 6, 3] Processed: [1,2]

Iteration 3: discover 4, queue = [6, 3, 4] Processed: [1, 2, 5]

Iteration 4: queue = [3, 4] Processed: [1, 2, 5, 6]

Iteration 5: queue = [4] Processed: [1, 2, 3, 5, 6]

Iteration 6: queue = [] Processed: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Done

The order in which BFS discovers the vertices is 2, 5, 6, 3, 4, in order of how far they are from the initial vertex 1.