From Stateful to Stateless: Building Web Apps That Scale

A Practical Guide to Managing State and Building Scalable Web Applications.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to the 155th issue of the Polymathic Engineer newsletter, the first in the new year.

The front-end layer of a web application is where the battle for scalability is won or lost. Every user interaction, every click, every API call flows through this layer. It is your first line of defense and the component receiving the most traffic.

The front-end layer has to deal with the most traffic and concurrent requests of any part of the system. One hundred users might be manageable. A thousand users start getting interesting. But what do you do when you need to serve 10,000 users at once? Or one hundred thousand?

The traditional approach of buying bigger servers hits a wall sooner or later. You can only scale vertically so far before you run out of RAM, CPU cores, or budget. Adding more servers to handle the load is the only way to keep going.

However, you can’t simply add more servers if your architecture won’t allow it. The reason is the state. State is any data that makes one server different from another. It could be session data stored in memory, files saved on local disk, or locks held by a specific process.

When servers hold state, users are tied to particular servers. This means that Requests can't be sent freely to different servers, servers cannot be cloned or replaced without downtime, and auto-scaling becomes a nightmare.

The solution seems simple: remove all state from your front-end servers. Make them completely interchangeable clones. But simple doesn’t mean easy. In this article, we will explore the most common types of state that sneak into web applications and the practical strategies to eliminate them.

The outline will be as follows:

Stateless vs. Stateful

Managing HTTP Sessions: Three Approaches

Managing Files: User Content and System-Generated Data

Managing Other Types of State

Project-based learning is the best way to develop technical skills. CodeCrafters is an excellent platform for tackling exciting projects, such as building your own Redis, Kafka, a DNS server, SQLite, or Git from scratch.

Sign up, and become a better software engineer.

Stateless vs. Stateful

Before talking about specific solutions, we need to understand what makes a service stateless or stateful. The difference is simple but very important.

A stateless service doesn’t hold any data between requests. It processes each request independently, without relying on information stored from previous requests. All the data needed to handle a request comes from either the request itself or from external storage.

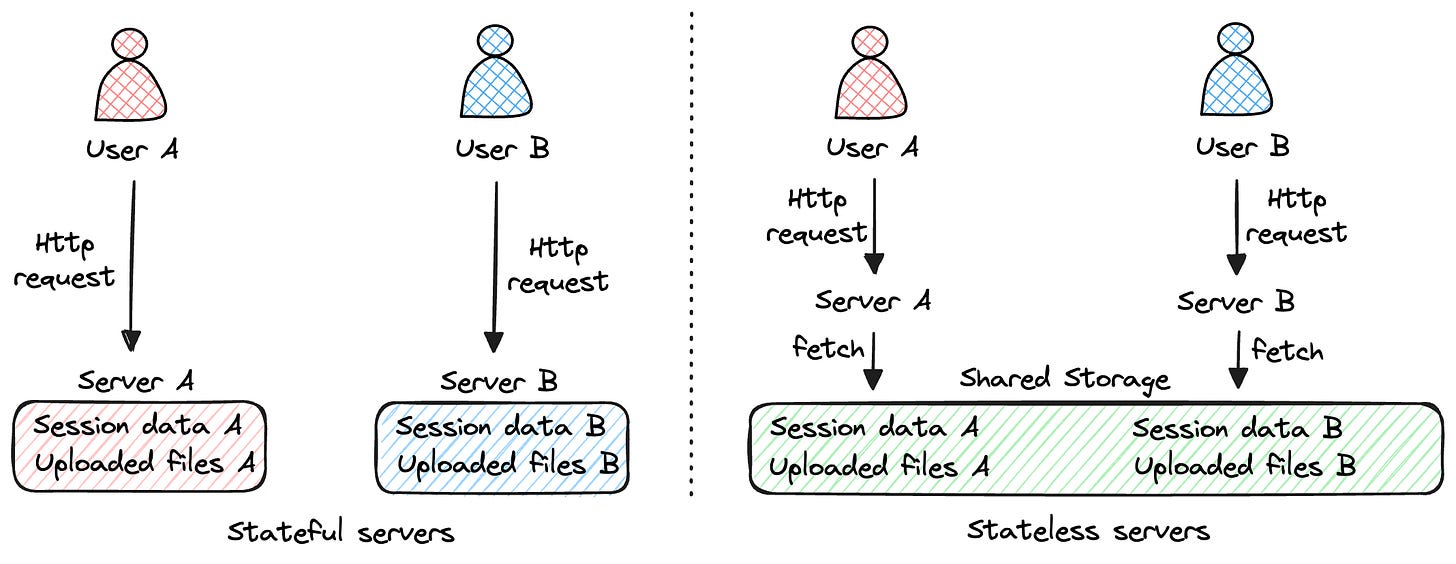

A stateful service, on the other hand, keeps data between requests. Other instances of the same service can’t see this data because it’s stored locally, like in memory, on disk, or in local variables.

The key difference is interchangeability. From the point of view of the client, stateless service instances can be swapped out at any time. The client can send a request to any instance and get the same result. Stateful services instead force clients to stick to the same instance, because that’s where their data is stored.

Let’s use an analogy to make this concrete. Imagine you’re visiting a coffee shop chain with multiple locations across the city. In this analogy, the chain is your website, each location is a server, and ordering a coffee is making a web request.

If the chain coffee shop is stateless, you walk into any location, place your order, pay, and receive your coffee. You provide all the necessary information with every order: what you want, how you want it done, and how you want to pay. The barista doesn’t need to know anything about you. You can go somewhere else tomorrow and get the same service. Each transaction is complete and independent.

Things are different if each shop in the chain keeps a physical loyalty card for each customer that the barista needs to stamp after each purchase. Now you are tied to this specific location. If you visit a different branch of the same shop, they can’t honor your loyalty card because it is not in their system. You need to return to your original location to use the stamps you’ve accumulated. The chain coffee shop became stateful.

The state's implications for scalability are enormous. With stateless servers, you can add or remove servers whenever you want. Traffic can be distributed evenly across all instances. If a server crashes, you just route requests to another server without losing any data, since none was stored there in the first place.

With stateful servers, everything becomes complicated. There must be ways for users to always get to the right server. It is not easy to get rid of servers because users' data would be lost when they are removed. Users are locked into certain instances, so you can't easily distribute the load.

Managing HTTP Sessions

Most web applications need to keep track of users across multiple requests. You log in once, and the site needs to remember you as you browse across different pages. When you add items to a shopping cart, they need to stay there.

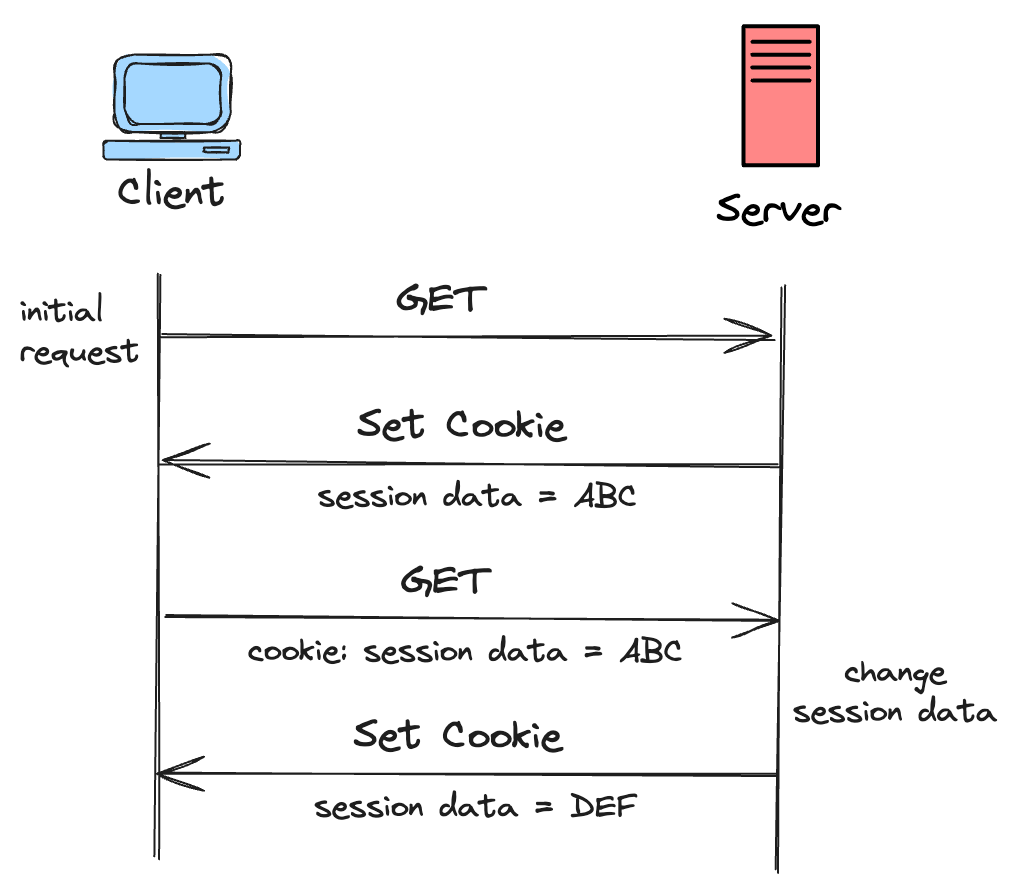

However, data exchange on the web relies on HTTP, a stateless protocol. Each request is independent, and HTTP doesn’t retain any information about previous requests. To work around this, web applications use cookies to create the illusion of a session.

Here is how it works. When a user first visits a website, the server sends back a small piece of data called a session cookie. The browser stores the cookie and sends it with every request to that site. The server then uses the session ID in the cookie to figure out which requests are from the same user and belong to the same session. Even when multiple users connect from the same IP address, cookies let the web server figure out which requests belong to which user.

Now, each session has associated data, such as the user ID, preferences, shopping cart contents, or the page the user was last viewing. This session-specific data needs to be available on every subsequent request so the application knows who is logged in and can personalize their experience.

But where does this session data actually live? If it lives in the memory of a specific web server, the user is stuck with that server. All the requests need to go to the same machine. You can’t freely distribute traffic and easily add or remove servers, and you have created a stateful system.

There are three practical approaches to avoid this, each with different tradeoffs:

Put Everything in Cookies. The most straightforward approach is to store all session data in the cookie itself. Instead of the cookie containing just a session ID, it includes the actual data, encrypted and encoded. When a request comes in, the server reads everything it needs from the cookie. When sending a response, it updates the cookie with any changes. This works beautifully when your session data is small, such as a user ID, a security token, and a few preferences. Overhead is minimal, and you avoid the complexity of managing external storage. The problem comes when you need to store more data. Browsers send cookies with every single request, and if your session data is 5KB, that’s 5KB added to every request and response. On mobile connections, this adds up quickly. To make things worse, consider that after encryption and encoding, your data grows by about a third.